If there was one thing that still united citizens of the Communist block in the early 1990s, it was the widespread hope to escape the Soviet drab, says Johannes Mueller, Head Of Research Macro Research, DWS Group.

No matter their disparate nationalities or their age, citizens hoped for a "normal" life of the sort most citizens of the democratic societies in the "West" take for granted.

Getting richer, but also being able to read and think what you want, and say or write what you think, without the fear of government oppression or foreign invasion.

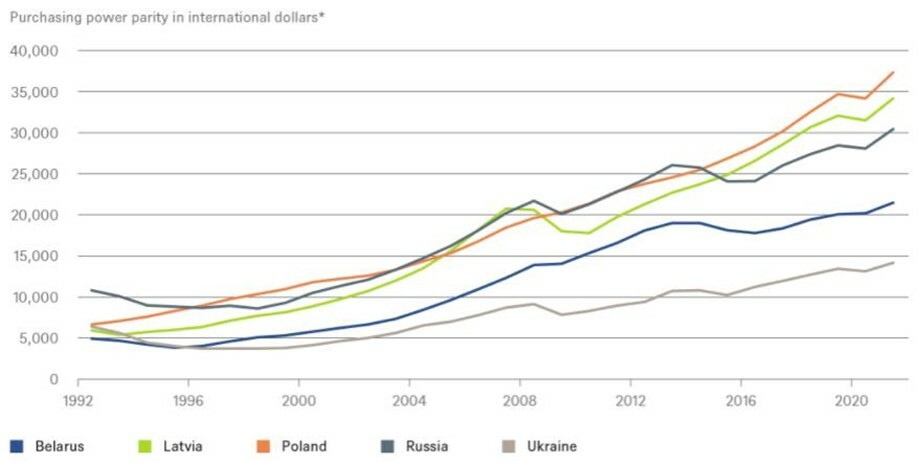

In purely economic terms, some countries have succeeded better than others, 30 years on, as our "Chart of the Week" illustrates. Measured at current prices and purchasing power parity, it shows that at the end of Communism, Ukraine had roughly the same gross domestic product (GDP) per capita as Poland. Today, it is only a fraction. Poland has even surpassed commodity rich Russia by a decent margin. The same is true of Latvia; the other two Baltic states have done better still.

This probably understates Russia's economic performance from the point of view of its average citizens, not only because of higher income levels than most to begin with, as the imperial and industrial center of the old Soviet bloc. Since 1990 the distribution of income and wealth appears to have become extremely unequal; some estimates suggest that the amount of private wealth siphoned offshore over the years by the very richest Russians stood at about three times the official net foreign reserves by 2015.

For critical Russian journalists deemed incorrigible enemies, the reprisals, intimidation and, ultimately, murders of, began almost immediately upon Putin's initial ascent to power.

For most other Eastern Europeans, notably in Poland and the Baltic states, membership of the European Union (EU) offered an alternative model of how to combine economic with political freedom.

Russia's first invasion of Ukraine in 2014 was sparked by a trade treaty with the EU, not by any realistic prospect of joining NATO. Similarly, the main demands among democracy activists in neighboring Belorussia that prompted the Moscow backed crackdown were better relations with the EU.

Contrary to what Putin seems to think, Ukrainians have long seen themselves as a clearly separate, European nation still in the process of defining where it stands vis a vis its neighbours.

And if that wasn't provocation enough, they want to determine their own future through free and fair elections - as it is normal in most of Europe. That Putin sees it a mortal threat says as much about his regime as the terrible scenes of cities getting bombed the world is currently witnessing.

30 years after the end of Soviet Communism, EU membership has proven a key factor in determining economic performance.

Sources: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, DWS Investment GmbH as of 10/31/21

*Gross domestic product per capita in current price