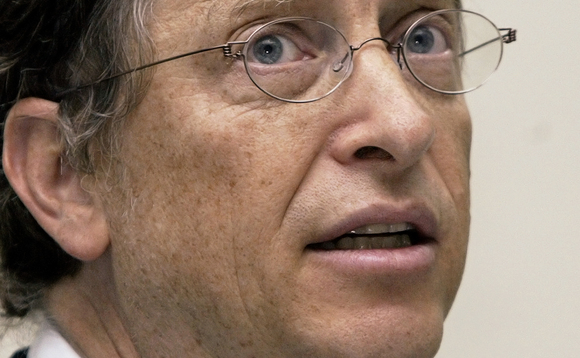

On 2 August, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates and Melinda French Gates finalised their divorce after 27 years of marriage. With their combined wealth thought to be c.$150bn, this is one of the biggest divorce settlements imaginable, say Emily Foy and Emily Grosvenor-Taylor.

Not only has it involved the disentangling of wealth of epic proportions, including business investments, land and property (alongside classic cars and artwork) but, also, the fact that a third of the wealth, over $50 billion, is held within the Gates Foundation, widely considered to be the largest philanthropic organisation of its type in the world.

The Foundation, which is established as a US nonprofit organisation, was established in 2000 with the aim of helping people to lead healthy, productive lives and to provide access to resources needed to succeed in life.

When announcing their separation in May, the couple indicated their intention to continue to run the Foundation together for a trial period of two years on the understanding that if they felt unable to continue in their roles thereafter, Ms French Gates would resign her positions as co-chair and trustee and Mr Gates would provide her with private resources to carry out her own philanthropic work, thus not affecting the assets of the Foundation.

The divorce took place in the US (under the laws of Washington State) but, with divorcees increasingly wishing to retain an ongoing business or charitable relationship and with increasing societal pressure on wealthy individuals to "give back" to the community, how might this affect divorce in England and Wales, and what issues need to be taken into account when dealing with the ongoing charitable or business interests of a separating couple?

When considering the parties' financial positions on divorce, the Court in England and Wales is required to consider how the financial obligations of each party towards the other will be terminated as soon after the final decree of divorce as the Court considers just and reasonable (s.25A(1) MCA 1973). This raises the question of how this would work practically in the context of ongoing obligations on both individuals to a joint interest in a charity or as co-trustees.

More specifically, how separated or divorced couples can continue to navigate a shared charitable interest and the steps that can be taken to ensure a smooth transition and sustained commitment to a shared cause.

Although the Gates Foundation as a US nonprofit is structured slightly differently to a typical UK charity and is not under the regulation of the UK Charity Commission, the fundamental principles will likely be similar; namely for the board of trustees to act collectively to help the charity achieve its purposes for the public benefit.

In order to maintain good governance, it is fundamentally important to ensure that a charity board works effectively as a team. As part of this, one key principle is that the board continually reviews its composition.

The board of the Gates Foundation is currently very small, with Mr Gates and Ms French Gates being the only trustees and co-chairs of the Foundation. Although the current position appears to be amicable, there is clearly a risk for strategic direction and decision-making if there are no other board members.

In the case of most UK charities, and most likely the Foundation, key decisions should be passed by a majority of the trustees. If there are only two trustees who are unable to agree then it can directly affect the operation of the charity and its ultimate beneficiaries if there is a deadlock.

It is therefore no surprise that in July 2021, the Foundation announced that the co-chairs have decided to expand the number of trustees overseeing the Foundation's governance and decision making as a family charitable trust.

The appointment of independent trustees is a key consideration for any charity to ensure that members can bring in new, fresh perspectives and that the board does not comprise trustees who are all friends of one (or both) founders and are unlikely to challenge their views or side with one trustee. In the situation where the founding trustees are divorced, it will be crucial to ensure that the board has enough independent trustees to guarantee effective decision making if they are unable to agree.

Therefore, the recruitment of new trustees will likely focus on key skills, knowledge and experience to ensure effective decision making as a board and diversity of thought. It may be that a charity will also consider its policies or governing documents as part of a governance review if trustees are separating. For example, it may re-visit the organisation's conflict of interest policy to determine when conflicted trustees should abstain from board decisions or whether the chair should have a casting vote.

The importance of independent board members was recently made clear in the landmark Supreme Court decision in the case of Lehtimäki and others (Respondents) v Cooper which again emerged after another high-value divorce.

Sir Christopher Hohn and Jamie Cooper, who jointly founded the Children's Investment Fund (CIFF), (one of the UK's largest charitable companies with assets worth over $4billion) decided that they were unable to manage the charity together after their marriage broke down.

They agreed that in exchange for a grant of $360m to a new charity founded by Ms Cooper, she would resign as a member and trustee of CIFF. The board had to agree to this grant but CIFF only had three members, two of whom (Sir Christopher and Ms Cooper) were conflicted and had to abstain from voting. The third trustee was Dr Marko Lehtimaki, who was a friend of Sir Christopher and had to make the decision.

The case worked its way to the Supreme Court, which held that members of charitable companies have fiduciary duties and Dr Lehtimaki therefore had to consider the best interests of CIFF's charitable objects as part of this duty. This case demonstrates the importance of independent trustees and the difficulty that can emerge with conflicted board members on a small board if the founders can no longer manage the charity together.

Therefore, for a separated couple navigating a shared charitable interest, reviewing the composition of the board and, if necessary, the recruitment of independent trustees will be an important step in order to ensure effective decision making and good governance, so that the charity can continue to achieve its objectives.

By Emily Foy, Senior Associate and Emily Grosvenor-Taylor, Senior Associate at Payne Hicks Beach